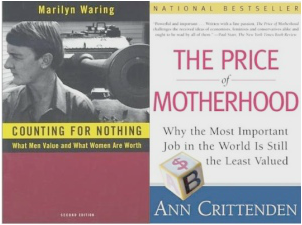

"Unpaid female caregiving is not only the life-blood of families, it is the very heart of the economy" Mother's Day is the big day of the year when people are supposed to buy things or do things for their mothers, or at least spare an appreciative thought for their mother if they are lucky to have a mother that they appreciate. However, there is an economic side to being a mom (or mum) and that's because the entire economy relies on new generations of being consumers born. Here's a free market think tank quote that inadvertently sheds light on this (and explains why there are often articles in the business media fretting that women aren't having enough babies): "Very often the best way to determine the contributions of people or things to an on-going process is to see what happens in their absence." —Jackson Grayson, The Illusion of Wage and Price Control, Michael Walker editor, published by the Fraser Institute (1976) Without the unpaid work of mothers and others, no paid work would be possible. Marilyn Waring in her ground-breaking book "Counting for Nothing" describes in detail how it is the very work defined under the GDP as being 'non-productive' that is the prerequisite for all other work. GETTING PAID IN HUGS But shouldn't mothers just be happy they get paid in hugs? This idea would only work if you could also pay your bills in hugs and if society agreed everyone else should also be paid in hugs. But as Ann Crittenden states: "Virtues and sacrifices, when expected of one group of people and not of everyone become the mark of an underclass." (The Price of Motherhood 2001) Society (and the environment) has a huge problem when those doing essential and beneficial work like raising children or other types of unpaid care work are financially penalized, but at the same time many harmful industries reap big financial rewards because they are considered 'productive' under the GDP (the easiest examples being the tobacco and junk food industries). The idea that your "productiveness" as defined by out-dated economic ideas determines your right to a decent life is clearly outdated. But it is not only mothers who suffer from the "unproductive" label. As automation replaces human labour with machines, more people will fall into the "unproductive" and "unpaid" category. This is why everyone from unpaid carers to those concerned about technological unemployment are saying that a universal basic income is the only practical solution to these problems. Read the full Mothernomics articlemhere. See Marilyn Waring's NFB documentary "Who's Counting" here.

0 Comments

It's common in our society for assumptions about personal worth to be based on how much income someone has, what work they do, and other external measures of wealth, status, or lack thereof. People on the low-end of 'The Money Measuring Stick' constantly have to resist negative assumptions that are projected upon them. Even though most people know "The Money Measuring Stick" is completely artificial, they still have to deal with this deeply flawed measure. They either use this stick on themselves and feel they don't 'measure up' to societal norms – which are media driven and sky high compared to the actual income numbers – or they use this stick on others (knowingly or unknowingly) and make judgements based on indications of wealth and status. That is why being asked "What do you do?" can often be a loaded question. William Bratt specializes in trauma counselling and counselling for men in Victoria BC and wrote an article about how to resist being defined by our jobs. He writes: "Unfortunately, the question 'So what do you do?' is likely to fall short of inviting people to share the coolest, most interesting things about themselves. When we lead with that question, we’re far more likely to pigeonhole people based on assumptions we have about their particular line of work." In May 2014 I interviewed him to discuss the topic further. Here are some of his insights: "People respond to expectations from society; they will sometimes lie when asked 'What do you do?' to avoid having others drawing negative conclusions about their value or worth. In my experience personally and professionally that question is a big one. This question can come from a culture of competition and some people can have tremendous anxiety about answering. People are concerned about themselves in relation to other people. They know people equate who you are with how you make money. Certain occupations are privileged; mainstream society sees some occupations as more desirable and assumptions are made about people based on that. People like to be seen as having dignity and they will resist a negative assumption based on how they make money. But there are so many other aspects of our lives that this question fails to acknowledge It’s a limiting question. I try to avoid asking it." He also emphasized that people are not just affected by societal expectations, they also find ways to resist. " One fellow who had retired from a long and successful career, started to worry he would lose value in the eyes of his mate. His act of resitance to this feeling was to take on a lot of handy work and renovations around the home." "Younger guys feel a lot of pressure to be seen in a certain light in society. There's a bias in our culture that we need to make money in ways that we are passionate about, but most people in the world are not so fortunate to do that. Work doesn’t have to be this grand 'vocation as calling'. It can be a means to an end. People can work to be able to do something they are more passionate about." I also interviewed a young 'millennial generation' retail worker for his experience with the 'What do you do?' question: "It really bothers me when I’m meeting someone for the first time and they immediately ask ‘So, what do you do??’ I find that question rude. I understand it is a conversation starter, but if someone you just met within 30 seconds wants to know what you do for work….They may as well ask me what kind of car I drive, how big my house is, or just ask to see my bank account. It comes down to money: everyone is curious how much money other people are making. It is impersonal. I can see the eagerness in their eyes waiting to be ...impressed? ...disappointed? ...happy they are doing better than me?" "I’m now at the point where being asked 'What do you do?' instantly makes me want to end the conversation. Most of the time when people ask, it isn’t coming from a good place, it's something used to judge you based on how ‘good’ your job is (or god forbid you don’t have one) or so they can brag about what they do for work. If someone is genuinely interested in getting to know me, then why not ask, ‘so what kind of stuff are you into?’ or ‘what do you enjoy doing?’ Later on if I feel like opening up, I can talk about what my ‘slave title’… oops I mean ‘job title’ is. Don’t get me wrong –I’m happy for anyone who has a job that they are proud of and wanting to share right away– but it does not mean that everyone you meet is in the same position. Perhaps my feelings on this will change once I have a job that I am proud of and reflects who I am and what I’m interested in. But most people aren’t working their ‘dream job’. It should be up to them if they want to share information about their work, they should not be put on the spot to explain. It doesn’t surprise me that people choose to lie about their profession–- I say, the people asking that question too soon deserve to be lied to. For many people what they do to make ends meet isn’t a happy story -–and it isn’t what defines who they are." Conclusion: The question of "What do you do" is often just another way to rank people with 'The Money Measuring Stick'. And it is clearly time we tossed this tendency to equate personal worth with monetary worth into the (rather full) dustbin of embarrassing human history. It is a harmful, artificial and inaccurate attempt to gauge someone's value as a person. Using it on others is superficial and simplistic. But using 'The Money Measuring Stick' on ourselves is dangerous because money, jobs, and status are external sources of self-worth, and all external sources of self-worth are fleeting and unreliable because they can easily and unexpectedly be lost. What's not superficial and artificial? Asking people what makes them happy; what are their hopes and dreams for themselves or humanity; what do they have a passionate interest in; what are their skills and hobbies; what do they like learning; what are their favourite books, art, movies, music; who are their mentors; are they part of a movement to make the world a better place? There are many, many more interesting ways that we as humans can relate to each other than blunt competitive assessments of subjective wealth. We don't need to use a money measuring stick when there are infinite possibilities instead. Related readings:

To Have or To Be by Eric Fromm Somebodies and Nobodies - Overcoming the Abuse of Rank by Robert Fuller Married to the Job by Ilene Philipson Wages by John Armstrong The Manly Mythology of Work The Theory of the Leisure Class by Thorstein Veblen Keeping Up Appearances (TV Tropes) - TV comedy series "So, what do you do?" an article that interviews young women in Vancouver about 'job shame' because they have jobs they hate. |

AuthorMy Opportunity & Help Book BC Categories

All

Archives

December 2020

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed